Local folks recall their days with Jimmy Carter

Former President Jimmy Carter teaching Sunday School a decade ago at Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains. [ Denise Butler | Contributed ]

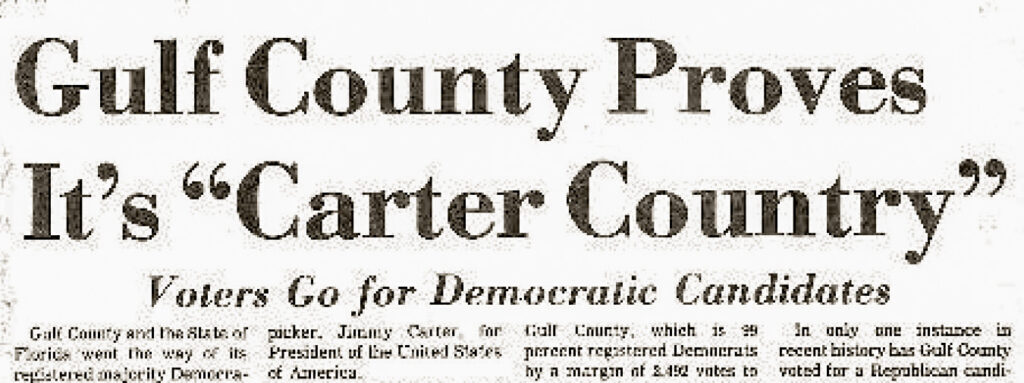

Former President Jimmy Carter teaching Sunday School a decade ago at Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains. [ Denise Butler | Contributed ] A headline in The Star after Jimmy Carter swept Gulf and Franklin counties en route to the presidency. [ The Star ]

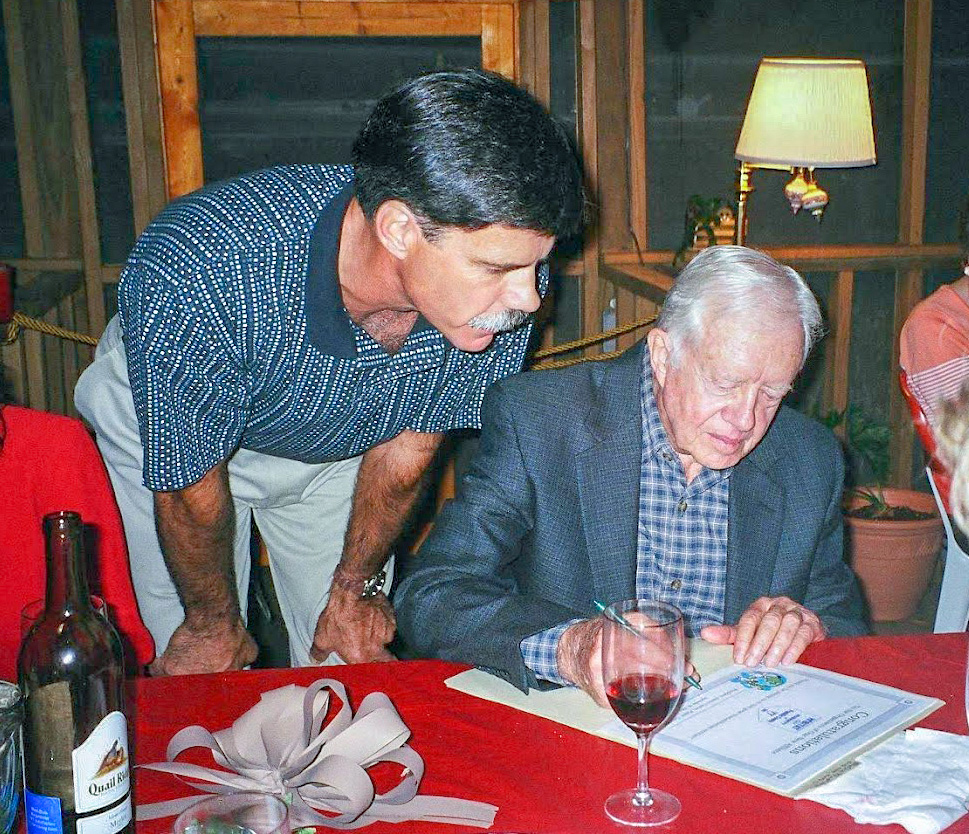

A headline in The Star after Jimmy Carter swept Gulf and Franklin counties en route to the presidency. [ The Star ] Carrabelle’s Skip Frink stands at left at a birthday party for Jimmy Carter as the former president signs a congratulatory letter for Franklin County’s new Habitat for Humanity chapter affiliate in September 2003. [ Skip Frink | Contributed ]

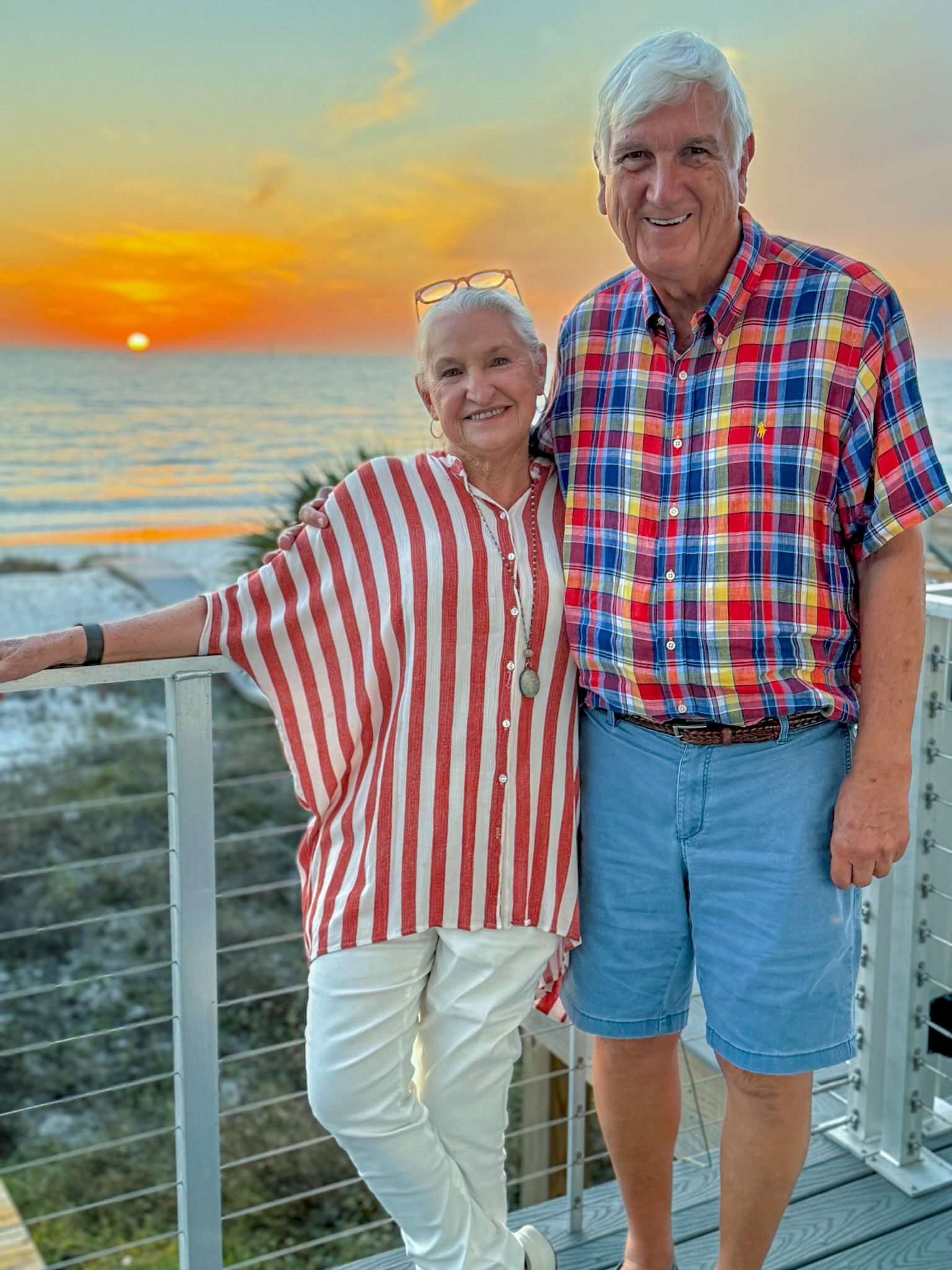

Carrabelle’s Skip Frink stands at left at a birthday party for Jimmy Carter as the former president signs a congratulatory letter for Franklin County’s new Habitat for Humanity chapter affiliate in September 2003. [ Skip Frink | Contributed ] Kathy Frink, left, chats with former First Lady Rosalyn Carter’s birthday party in September 2003. [ Skip Frink | Contributed ]

Kathy Frink, left, chats with former First Lady Rosalyn Carter’s birthday party in September 2003. [ Skip Frink | Contributed ] Denise Butler, left, and husband Cliff Butler, right, stand with Jimmy and Rosalyn Carter at Maranatha Baptist Church a decade ago.[ Denis Butler | Contributed ]

Denise Butler, left, and husband Cliff Butler, right, stand with Jimmy and Rosalyn Carter at Maranatha Baptist Church a decade ago.[ Denis Butler | Contributed ]

In 1976, when the peanut farmer from Plains, Georgia first ran for the presidency, and again in 1980, when he sought a second term in office, Jimmy Carter was the clear favorite of what was then an overwhelmingly Democratic Forgotten Coast.

In Gulf County, Carter captured 63 percent of the vote, and in Franklin it was 64 percent, as he defeated incumbent Republican Gerald Ford in 1976.

Four years later, the percentages in favor of Carter were much the same along the Forgotten Coast, although this time Republican Ronald Reagan defeated him for the presidency.

Forty-five years later, Gulf and Franklin counties are now solidly and reliably Republican with a Democratic candidate standing little chance of carrying them in a presidential election, let alone garnering close to two-thirds of the vote.

But, as the nation prepares to bid a final farewell to Carter, who died this month at the age of 100, there remains a genuine affection for a man who touched many lives here, both politically while he was in office, and socially and culturally in the many years he redefined the activism of a post-presidential life of service.

“It was a great experience,” said Eastpoint’s Denise Butler, who along with husband Cliff was among the many people who in recent years ventured up to Plains, Georgia to take in one of Sunday School lessons that Carter regularly gave at Maranatha Baptist Church.

“It was humbling to see a man like that who had been in the highest reaches of power,” she said of her 2014 trip.

The Butlers had heard about these Sunday Schools he was teaching, and while they knew there was no guarantee that he would be available on a given Sunday, they arranged for their trip anyway.

“You went and just took your chances,” said Denise. “We went to Americus the night before and then had to be there very, very early. It was absolutely pouring rain the day we went.”

After undergoing Secret Service scrutiny, complete with accompaniment with German Shepherds, the Butlers managed second row seats, and listened carefully as Jan Williams, who was daughter Amy Carter’s fourth grade teacher, explained to the packed assembly of attendees what would happen.

“He’s going to say good morning and you’re going to say good morning back,” Williams told them. “Tell him your state or country. She made us practice how we were supposed to answer.”

Carter, who walked in calmly, absent any fanfare, spoke about human trafficking, about how Atlanta was an epicenter in that part of the county. “He was very soft spoken, very genteel. You could see that he was an old man, so slightly built. But he spoke clearly and strongly, succinctly and intelligently. He was very with it, even at 90.”

Those who wanted to have a photo with the former president had to attend the entire service, and afterwards were given an opportunity to take a single photograph.

“Rosalyn noticed Cliff’s rotary pin and they both spoke to us,” Denise said.

Afterwards, many of the attendees went to “a hole in the wall diner, nothing fancy for sure” in Plains for Sunday dinner, complete with red vinyl trays, said Denise.

Later on, the Carters stopped in, accompanied by the Secret Service, and they conducted themselves like average patrons.

“They were so down to earth, going down the line with a red vinyl tray just like everybody else,” Denise said. “Everybody was so respectful but you felt like you could say ‘Hey Mr. Jimmy how’s it going?’”

In the case of Carrabelle’s Skip and Kathy Frink, their brush with the Carters came in 2003, in part due to their operation of the Old Carrabelle Hotel.

Plains Mayor Boze Godwin and wife Betty, who had grown up with Rosalyn, often stayed at the hotel, and so on the occasion of their hosting a 79th birthday party for the former president they invited the Frinks for the Sept. 29. 2003 affair.

That year, Frink was among several local folks who, with the support and encouragement of The St. Joe Company, laid the groundwork to start a Habitat for Humanity affiliate in Franklin County. Cliff Butler, a former banker, served as treasurer for the fledgling affiliate, which was assisted by former St. Joe Company exec Billy Buzzett. Builders Wayne Thomas and Mason Bean were a part as well, as were Max Brown, the first president; and Don and Pam Ashley.

Held on the screened-in porch in the Godwins’ back yard, the party was attended by about two dozen people, including seven Secret Service agents, one on the roof of the house.

When the Frinks drove up, they were met by a man in a coat and tie, and they told him who they were. “We know exactly who you are,” he told them. “That was a real dose of Secret Service there.”

Frink had prepared an informal document, nothing official, congratulating Franklin County on inaugurating the new Habitat for Humanity that Carter, a longtime volunteer with the organization, gladly signed.

In terms of political involvement with Jimmy Carter, St. Joe Beach’s Zebe Schmitt, and her partner Richard Harden, both had extensive dealings with Carter both during his term as Georgia governor and during his presidency.

A teacher and administrator by profession, Schmitt had polio as a child, and in addition to several surgeries, had visited Warm Springs on several occasions for therapy.

After working on Carter’s successful gubernatorial campaign, she stayed involved with Carter’s work on behalf of the disabled and followed closely the transition of ownership from President Roosevelt’s Georgia Warm Springs Foundation to the state of Georgia.

“Later he chose to kick off his race for president at Warm Springs, as people all over the country had an attachment to Warm Springs,” she said. “I became much closer to him and to what they were doing.”

Later, Carter would create and become the honorary chairman of the Georgia Council of Development Disabilities, which Schmitt called the nation’s “first true consumer driver council” for advocacy and awareness of issues affecting the disabled.

“I with great pride was able to spread that word through national channels,” she said.

“Personally because of my history with polio, I just cannot believe how much he (Carter) has done for the world, in every country taking vaccinations to every child that he could,” Schmitt said.

“He was an amazing man who cared, who cares more for others than he does for himself,” she said. “He always put others first and he worked so hard to give of himself. That’s the model we’re missing now.”

Her life partner of the last seven years, Richard Harden, worked even more closely with Carter as a director within the administration.

In December 1977, after working on the campaign, Harden, at age 33, was appointed by Carter as his special assistant for information management, as director of the office of administration.

Harden had worked for the accounting firm of Arthur Andersen, and was familiar with what Carter had done in reorganizing Georgia government through the workings of a task force of people from both the private and public sectors.

One key item that he notes from his work with Carter on both the state and federal levels was the effort to do zero based budgeting, a method now popular with fiscal conservatives in which all spending is analyzed from the bottom up and justification is needed if it was to continue from one year to the next.

Harden said Carter was typically very hands-on in his administrative processes. “He would provide feedback,” he said. “If you wrote him a memo about a particular topic, you’d get it back with handwritten notes, citing particular paragraphs. I once sent him a note and (at one point) he wrote ‘You’re obviously biased.’

“He paid attention to the details and he read things and he’d give you feedback, it was a very nice way to work with somebody,” said Harden. “When you did something he praised you, and he corrected you when he thought it was wrong.”

One perk of Harden’s position was that he was often the point person in working closely with Miss Lilian, Carter’s mother, who had served on boards in Georgia and took an interest in the Carter administration, becoming a Peace Corps volunteer later in her life.

“I got to know her and we became friends,” he said.

On one occasion, he and Lillian Carter arranged for a trip to California, where as a big Dodgers fan, they could take in a ballgame.

“We stayed with actress Shirley McClain and went to the Dodgers game and she and Shirley became big friends. (McClain’s brother) Warren Beatty stopped by while we were out there,” Harden said.

“He (Harden) cooked bacon for Shirley McClain in her kitchen,” Schmitt said.

On another occasion, Harden accompanied Miss Lillian on a trip to Africa and on another to Paris. “That was one of the fun parts of my job,” he said.

Harden, who together with Schmitt are attending the memorial services both in Georgia and in Washington, D.C. said he believes Carter’s legacy will be well-regarded in the years to come.

“I hope people see the example that he set for us and that more of us will follow that example,” he said. “He got some things started with the climate issues, and in the human rights area, trying to deal with that around the world. His life after being president is an example of what you hope people like that would do.

“As things get sorted out he’s going to be well thought of, not only in the US but around the world,” Harden said. “He was a fine fellow and he did a lot of good things.”

The highest ranking connection to the Forgotten Coast is that of Jack Watson, Jr., the older brother of Franklin County Tax Collector Rick Watson, who served as White House Chief of Staff to Carter from 1980 to 1981.

A Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Vanderbilt University, recipient of a law degree from and a captain in the U.S. Marine Corps, Jack Watson directed the transition team between Ford and Carter, and later rose in the ranks to serve as the president’s chief of staff.

In a 2003 article outlining Carter’s numerous achievements as president, from the Camp David accords to the creations of the energy and education department, Watson wrote that “Carter was a far more successful president than he is generally given credit for, and that the verdict of history on his presidency will be, as it has been for President Truman, one of admiration and respect.

“Carter’s whole adult life, from the Naval Academy, to his service as an officer in the U.S. Navy, to becoming an engaged, irrepressible senior statesman and intrepid builder of houses, has been dedicated to public service and the establishment ‘of justice in a sinful world,’” Watson wrote. “Carter believed passionately in the ‘idea’ of America and in the institutions and branches of our government that sustain it and make it work. He understood the importance of America’s leadership role in the world and had an abiding faith in the bedrock principles and values upon which our nation was founded.

“Carter is a fundamentally good and decent man, kind in the way he treats people, modest and unassuming in the way he lives his life; respectful of the views of others, including those with whom he disagrees; endlessly intellectually curious, constantly learning, honest and straight-spoken in his convictions of what is right, fair and just,” Watson wrote.

Meet the Editor

David Adlerstein, The Apalachicola Times’ digital editor, started with the news outlet in January 2002 as a reporter.

Prior to then, David Adlerstein began as a newspaperman with a small Boston weekly, after graduating magna cum laude from Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. He later edited the weekly Bellville Times, and as business reporter for the daily Marion Star, both not far from his hometown of Columbus, Ohio.

In 1995, he moved to South Florida, and worked as a business reporter and editor of Medical Business newspaper. In Jan. 2002, he began with the Apalachicola Times, first as reporter and later as editor, and in Oct. 2020, also began editing the Port St. Joe Star.