Rats, Ratso, and Ratatouille

“Rats!” Webster defines the interjection, a tad politer than “damn” or some other four-letter words you might let slip, as expressing “disappointment, frustration, or disgust.” The usage, which dates back to the 1800s, may be making a comeback with the widespread resurgence of rat populations, as reported by the NY Times, PBS, and other media.

A recent Orkin report of America’s 50 “rattiest” cities ranked Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City, and Washington, DC as the most infested, with NYC home to some 2 million rats and L.A. stricken in 2018 by a major typhus outbreak connected to rodent-born fleas.

But two Florida cities made the rat-roster too, with Tampa at #50 and Miami even rattier at #23.

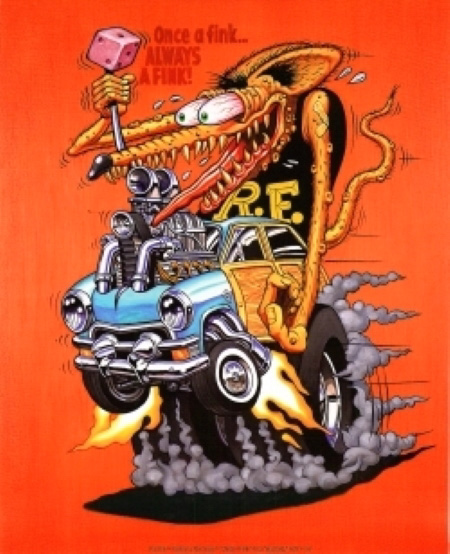

Most folks flat out despise rats. If you’re suspicious of someone, you smell a rat. A messy apartment is a rathole. The hectic workaday world is a rat race. You might or might not like rat-tail hair. Ratfink was 60s slang for a tattler, someone who rats on you: custom car aficionado Ed “Big Daddy” Roth popularized the term with his comic Rat Fink, an anti-hero parody of Mickey Mouse.

Dustin Hoffman’s character Rico Rizzo in the 1969 film “Midnight Cowboy” longed to rid himself of the moniker “Ratso” that his con-man misadventures had earned him on the street. Likewise, the 1971 movie “Willard” (and its 2003 remake), based on Stephen Gilbert’s novel “Ratman’s Notebooks,” did little to improve the image of rats, even those kept by eccentrics as companions.

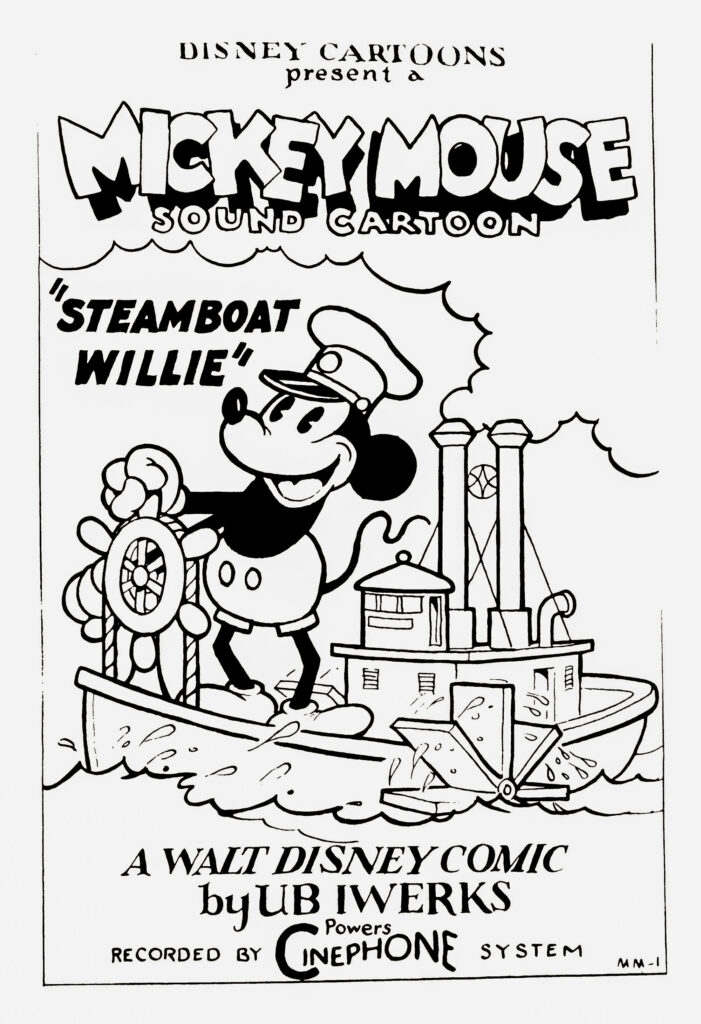

When I was 12 or so, I had my own pet mice and white rats, though not the murderous kind. In fact, these little guys get plenty of good press in our culture. Disney’s Mickey and Minnie Mouse are prime examples of the loveable rodent. Their original images from the 1928 cartoon “Steamboat Willie” (it’s on YouTube) were recently released from copyright after 95 years.

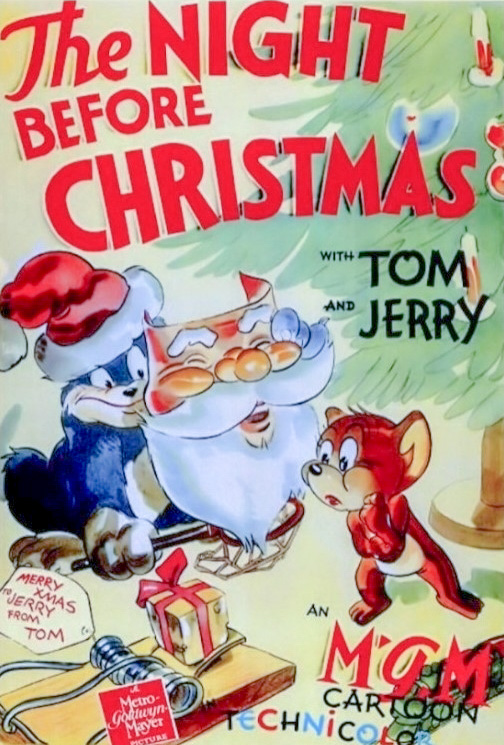

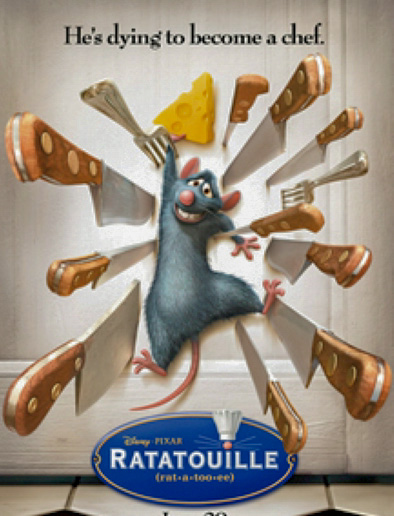

And let’s not forget Jerry, of the Tom and Jerry cartoons created by Hanna-Barbera in 1940. Or Terrytoons’ Mighty Mouse, originally “Super Mouse,” a Superman parody, also dating back to the 40s, and Andy Kaufman’s crooning the theme song: “Here I come to save the day.” More recently there’s Remy (voiced by Patton Oswalt), perhaps the most beloved cinematic rat of all time, the culinary hero of the 2007 animated film “Ratatouille.”

The ancient Romans had similarly mixed responses to these RODents. The scientific name for the mammal order Rodentia derives from a Latin word that means to bite, gnaw, eat away, and is source also of corRODe and eRODe. The ROD- root may be connected with RAT- in Late Latin rattus, our modern genus name.

Both rats and mice belong to the rodent family Muridae, and the Romans didn’t distinguish them except by size: what we call a “mouse” they called mus/muris (hence MURidae), and a rat was just a big one (a magnus mus). A tiny mouse was a musculus, a word Roman physicians humorously adopted for what we call MUSCLe, presumably for the little subcutaneous flexing movements muscles make.

The Romans would call someone a mus as an insult (like our “you dirty rat!”) or as a term of endearment (like “my sweet little mouse”). The poet Horace, who gave us carpe diem (“harvest the day”), also retells Aesop’s fable of the City Mouse and the Country Mouse.

We have from the ancient Greeks another delightful tale, the Batrachomyomachia, a mock epic about a battle between mice and frog warriors (the mice win!) – a lively, charmingly illustrated new translation by Alicia Stallings is available on Amazon. Mice have a role in an earlier, more serious epic: in Homer’s Iliad, Apollo “Smintheus,” taken by some to mean “Mouse-God,” punished the Greeks with a plague possibly spread by mice.

While rats, or the fleas infesting them, certainly can transmit diseases (the CDC has identified about a dozen connected to rodents), the critters have also proven beneficial to medical researchers and other scientists. From the 19th century onward, the use of rats in experimentation has led to breakthroughs in studies of genetics, diet, human behavior and intelligence, the efficacy of drugs, as well as in treatment of diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, and other diseases.

With their intelligence and keen sense of smell, rats have been put to work in such tasks as identifying tuberculosis in patients and detecting landmines. In some African and Asian cultures, rats are a source of food; Brits in the Victorian Age ate rat-pies; and rat cuisine has appeared on occasion in the West Virginia Roadkill Cook-off and Autumn Harvest Festival in Marlinton. Even the Romans considered the dormouse a delicacy and enjoyed them as hors d’oeuvres or dessert.

“When in Rome, do as the Romans do,” or so they say. But in this instance I think eating mice is not nice: how could I ever look Mickey in the eye?!

Rick LaFleur is retired from 40 years of teaching Latin and Classics at the University of Georgia; his latest books are The Secret Lives of Words, a collection of his widely distributed newspaper columns, and Ubi Fera Sunt, a lively translation into classical Latin of Maurice Sendak’s children’s classic, Where the Wild Things Are. He and wife Alice live part of the year in Apalachicola, under the careful watch of their bobtail manx Augustus.

Meet the Editor

David Adlerstein, The Apalachicola Times’ digital editor, started with the news outlet in January 2002 as a reporter.

Prior to then, David Adlerstein began as a newspaperman with a small Boston weekly, after graduating magna cum laude from Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. He later edited the weekly Bellville Times, and as business reporter for the daily Marion Star, both not far from his hometown of Columbus, Ohio.

In 1995, he moved to South Florida, and worked as a business reporter and editor of Medical Business newspaper. In Jan. 2002, he began with the Apalachicola Times, first as reporter and later as editor, and in Oct. 2020, also began editing the Port St. Joe Star.