War comes to our shores

Diver explores history of Empire Mica

A week shy of seven months after the day that will live in infamy marked the United States’ formal entry into World War II, an infamous night brought the war home to the Forgotten Coast.

Beginning just after midnight on Monday, June 29, 1942, about 21 miles due south of Cape San Blas, beneath a brilliantly moonlit sky, a German U-boat had been shadowing the Empire Mica, a British oil tanker on its way back from Texas with a complete load of 12,000 tons of oil of immense value to the Allies for products such as kerosene and aviation fuel.

“It is very bright,” Kapitänleutnant (Lieutenant Commander) Günther Müller-Stöckheim later wrote in his Daily War Diary, “but I hope he does not recognize (the presence of a U-boat) very much.”

At about 1 a.m. the Empire Mica just three-fourths of a nautical mile away, the commander of U-67 ordered the firing of two steam-driven torpedoes.

The horrific effect of the explosion would send the 463-foot-long tanker to the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico about 110 feet below, where it became the final resting place for 33 of the 47 sailors aboard the Empire Mica.

With Coast Guard auxiliary crews rushing to the scene, 14 of the sailors were rescued and taken to Apalachicola, with half of them transported to Panama City for medical attention.

The flaming head of war had flashed an evil grin into the faces of the Forgotten Coast.

In a fascinating presentation earlier this month as part of the Apalachicola Area Historical Society’s Spring Speak Series, diving enthusiast and amateur historian Grayson Shepard offered a detailed look at what took place at sea on that blood-soaked June morning.

Throughout his March 16 appearance, marked by a showing of several still images related to the wartime history, Shepard shared underwater video that he had taken when he and fellow diver Mandi Singer had explored the wreckage, now one of the most popular dive sites in Florida.

Shepard told of how the comparatively new Empire Mica, built just 11 months earlier, was returning from Baytown, Texas with a full load of oil. Captain Hugh Bentley opted not to take the 710-nautical-mile straight-line course, but instead steamed along the 100-fathom-curve hugging the Gulf Coast, tracking to the east-southeast and eyeing lighthouses marking where the coastline turned south at Florida’s Big Bend. Knowing he couldn’t enter St. Andrew Bay or St. Joseph Bay safely at night, Bentley was running behind schedule to meet up with a convoy and cut the corner.

The German U-boat, with its crew of 51, had guessed the Empire Mica’s route correctly, and the 249-foot sub, capable of moving at 7 knots submerged and 18 knots on the surface, readied to strike.

The two torpedoes that hit the Empire Mica found their target, and the ship burst into flames. Coastal lookouts in the lighthouse on Cape San Blas witnessed the explosion and telephoned Coast Guard Lt. Elgin Wefing, captain of the port at Apalachicola. The official Coast Guard vessel assigned to the Apalachicola area was in Panama City for repairs, so R.J. “Dick” Heyser, father of the man who would later become famous as the U-2 spy plane pilot whose photos triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis, volunteered his 32-foot Countess.

Wefing and Heyser, along with Coast Guard members Wade Grant and W.L. McCormick and civilians Belton Tarantino and Joe Thompson, sailed from Apalachicola at 2 a.m. to rescue any survivors.

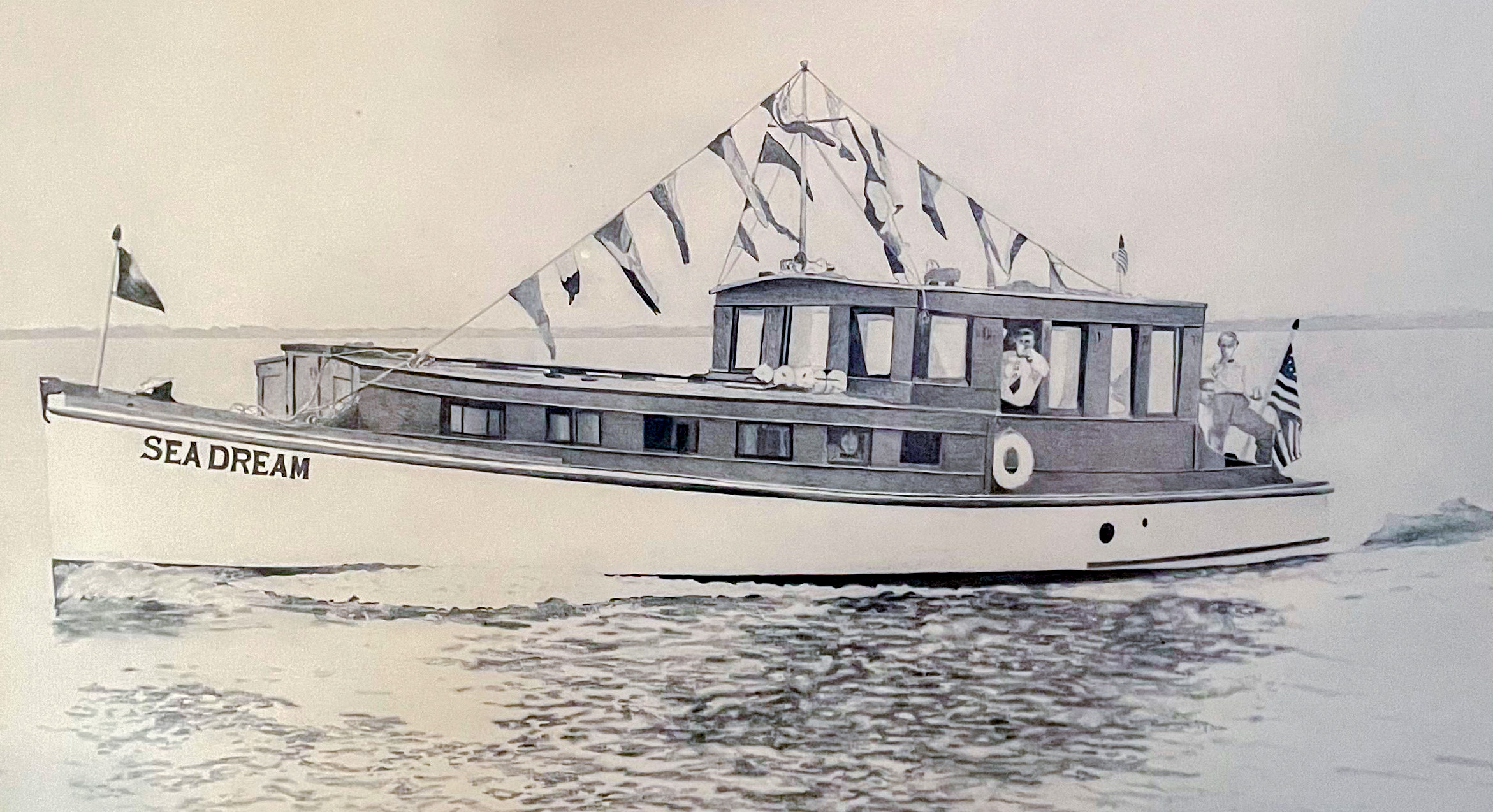

Soon afterwards, W.F. Randolph and John Hathcock left Apalachicola in Randolph’s larger and faster Sea Dream to assist the Countess and her crew with the rescue.

“Both crafts ran without lights because it was wartime,” said Shepard. “They used only the moonlight and the fire on the burning British tanker far out at sea to guide them. The trip took several hours.”

He said the Countess arrived first and found the Empire Mica adrift and ablaze with no

survivors in the water. The crew spotted a life raft with 14 survivors and took them under

tow. When the Sea Dream arrived, they circled the burning wreck searching for

additional survivors, but found none. They then caught up with the Countess, took the survivors onboard, and delivered them to Apalachicola’s Coombs Armory where a makeshift hospital had been set up.

Seven of the more seriously injured sailors were immediately transported to Panama City, while the remaining seven spent a week in Apalachicola where they were treated for their injuries and cared for by the local residents.

The Empire Mica burned and drifted for 24 hours until it sank at its current location

approximately 25 miles southwest of West Pass.

Meet the Editor

David Adlerstein, The Apalachicola Times’ digital editor, started with the news outlet in January 2002 as a reporter.

Prior to then, David Adlerstein began as a newspaperman with a small Boston weekly, after graduating magna cum laude from Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. He later edited the weekly Bellville Times, and as business reporter for the daily Marion Star, both not far from his hometown of Columbus, Ohio.

In 1995, he moved to South Florida, and worked as a business reporter and editor of Medical Business newspaper. In Jan. 2002, he began with the Apalachicola Times, first as reporter and later as editor, and in Oct. 2020, also began editing the Port St. Joe Star.