County dealt setback in Indian Lagoon suit

1st DCA says case must be heard in Tallahassee

The likelihood Gulf County will win its suit against the state that seeks to re-open Indian Lagoon to recreational oyster harvesting dimmed in August after the 1st District Court of Appeals overturned a circuit judge’s earlier decision.

In an Aug. 16 ruling, all three appellate judges – Lori Rowe, Susan Kelsey and Adam Tanenbaum – ruled that Circuit Judge Devin Collier was wrong in July 2022 when he concluded the plaintiffs, who are the Gulf County commissioners and Carmen McLemore as a private citizen, had a right to have the case heard in Gulf County.

Rather, the three judges ruled the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission retained the privilege to have the case in its “home venue,” and so vacated Collier’s ruling that would have kept it in the 14th Judicial Circuit and had it remanded to the court in Tallahassee.

“I’m disappointed the DCA overruled Judge Collier, but I’m not surprised,” said County Administrator Michael Hammond. “The chances of us beating the state in Tallahassee are very slim, unfortunately. That’s home field advantage for the state.”

In his original Feb. 2021 complaint, County Attorney Jeremy Novak argued the FWC was wrong when it decided in 2020 to include recreational harvesting in the Lagoon when it suspended all wild harvesting in Apalachicola Bay through 2025.

“No research has been conducted on the Lagoon to justify the need for its inclusion of the Bay system closure,” Novak argued. “The Lagoon’s inclusion… is based solely on one brief visit to the Lagoon by a local researcher who was not even able to adequately observe the system during that visit due to the Lagoon’s non-navigable waters.

“After a superficial observation on the banks adjacent to the Lagoon, the researcher concluded that the Lagoon ‘looked similar’ to the Bay and therefore should be closed as stated during the FWC public hearing on Dec. 17, 2020,” he wrote.

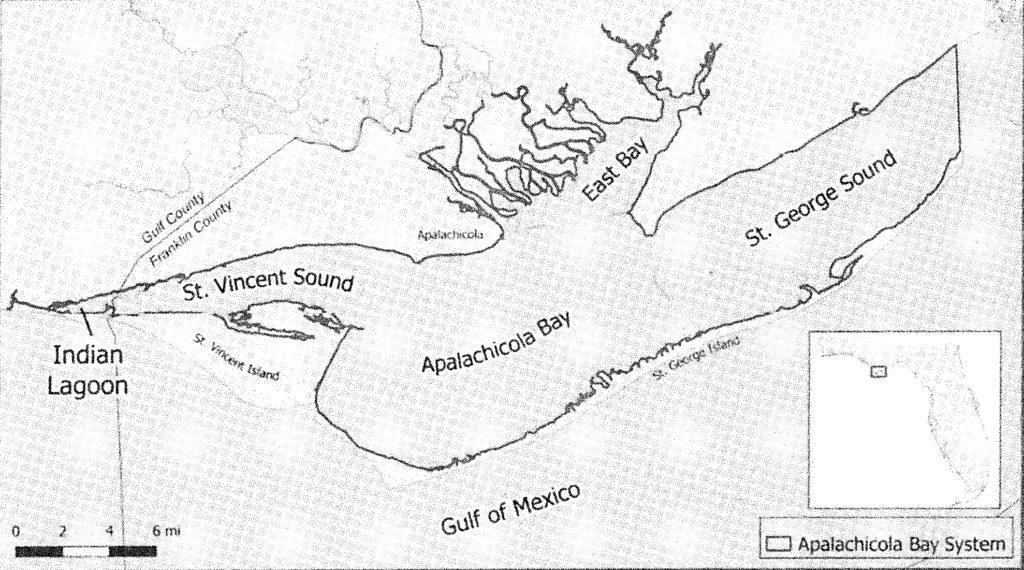

In contrast to Apalachicola Bay, which is a comparatively large body of water off the Franklin County coast that is heavily affected by freshwater flow downriver, Indian Lagoon “is a thick, muddy body of extremely shallow water” with a healthy population of oysters that make up just six-tenths of 1 percent of the Bay system, Novak contended.

“No commercial harvesting takes place in the Lagoon because of its minimal access,” he wrote. “Gulf County locals who harvest recreationally must tread through the muddy and shallow waters on foot and hand harvest the oysters, which is a labor-intensive process.”

“There was never any tonging in Indian Lagoon, and because it’s so shallow you couldn’t get a boat in there. FWC can’t get in with big boats,” said Hammond. “It was a way for the regular guy to pick up oysters.”

Regular guys like Carmen McLemore, 71, a former county commissioner, who used to go oyster hogging, essentially picking them up during low tide from the lagoon, together with his seven other siblings when they were kids.

“I just want it to open up for recreational use only,” said McLemore. “Let me go down there, without having to pay $1.50 a piece for farm-raised oysters. That’s what I’m fighting.

“With FWC, if they ever get their hands on something, anything they touch, they screw up,” he said.

The FWC’s closure of Apalachicola Bay does not affect the aquaculture industry either in Franklin or Gulf County, which is conducted on specific leases in the water and is not subject to the same rules as wild harvesting.

‘Sword-wielder exception’ does not apply

Novak said he had McLemore signed on as a plaintiff in the suit in order to “pierce the shield” that FWC retains as an overarching state agency.

“To get it local you have to have action against your constituency,” Novak said. “We had to show there was some harm. We included him to show there has been some right deprived to constituents.”

Collier thought the case was made that the matter fell under the so-called “sword-wielder exception,” which according to a 1980 case, occurs when “direct judicial protection is sought from an unlawful invasion of a constitutional right of the plaintiff, directly threatened in the county where the suit is instituted.”

But the DCA didn’t agree that mere closure of the lagoon constituted harm, and wrote that the exception does not apply if “the primary purpose of the litigation is to obtain a judicial interpretation or declaration of a party’s rights or duties under… rules and regulations.

“The only official act at issue here is (FWC’s) adoption of the rule itself,” the judges wrote. “(FWC) has not charged any of the appellees with a rule violation, and it has not fined or otherwise sanctioned any of them. There is no pending case alleging a rule violation, and (FWC) has not pursued enforcement or penalties.”

Novak said he believes FWC has avoided issuing any citations, knowing such action would have bolstered the county’s case to have it adjudicated in Gulf County.

He said the court delays related to Covid-19 have meant that a ruling on the merits of the case, such as whether the FWC did its homework in issuing the closure by holding an appropriate number of public in-person meetings, won’t come down until almost four years into the five-year closure.

“Sadly it defeats the whole purpose,” Novak said. “We’re just talking about mom and pop going to oyster. This was time sensitive, and when we looked for remedies it took the appellate division a year. Everything came to a grinding halt.”

County may open talks with FWC

The issue at hand now is how the county commission plans to proceed, in light of the fact that legal costs will continue to mount and the odds are lessened that it will ultimately prevail prior to the scheduled 2025 re-opening of the Apalachicola Bay.

Novak said the county can argue, as it has in the complaint, that “no substantive research was conducted to specifically address the Indian Lagoon….and a research-driven report for the FWC to determine the number of oyster spat, the health of the Lagoon’s ecosystem, or anything else that would allow for an accurate assessment of the need to close the entire Lagoon.

But, he said, “it’s a risk reward. It’s going to be a financial commitment, and it will be a year of (legal) discovery and we’ll be less than a year out (from re-opening the bay).”

Hammond said the commissioners will have to consider their options, particularly since history is not on their side given court battles over the net ban that were waged in Tallahassee.

“I think the county has to decide if the county wants to spend money and fight on their (FWC’s) ground,” he said.

One aspect of what could bear on any talks with FWC over dropping the case is the fact that in early 2020, FWC received a $20 million grant commitment from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) Gulf Environment Benefits Fund to conduct a large-scale restoration of the oyster habitat in Apalachicola Bay.

“FWC has not spent, nor has it advised or informed Gulf County of plans to spend any of the $20 million NFWF grant specifically on the Lagoon studies and restoration,” wrote Novak in the original complaint.

“What are you doing to protect oystering in Gulf County? Tell us where you’re spending the money,” he said.

“Can we get some concession out of them?” said Hammond. “We may have to say ‘What will you settle for?’ if it’s going to cost a lot.”

Meet the Editor

David Adlerstein, The Apalachicola Times’ digital editor, started with the news outlet in January 2002 as a reporter.

Prior to then, David Adlerstein began as a newspaperman with a small Boston weekly, after graduating magna cum laude from Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. He later edited the weekly Bellville Times, and as business reporter for the daily Marion Star, both not far from his hometown of Columbus, Ohio.

In 1995, he moved to South Florida, and worked as a business reporter and editor of Medical Business newspaper. In Jan. 2002, he began with the Apalachicola Times, first as reporter and later as editor, and in Oct. 2020, also began editing the Port St. Joe Star.